Last Updated: 3/26/2023

Further Reading:

- Chapter 18 of Age of Extremes by Eric Hobsbawm

- Avant-Garde and Kitsch by Clement Greeneberg

What is art? Over a hundred years ago — in the era of Repin and Monet — this would’ve been a lot easier of a question to answer. There was a very specific form that art was associated with (painting/sculpture), a very specific function, a very specific meaning, and very specific conventions when it came to its content and expression. If I showed Napoleon a Michelangelo, he would not doubt for a second that it was a work of art.

However, in the modern age we can’t really take that for granted anymore. On a conventional and aesthetic level, avant-garde and postmodern movements very much consciously pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable. Technology shook things up formally in that radio and television would come to dominate as the artforms of the century. The economics of art shifted from a past-time of the educated aristocracy into the domain of the middle-class markets. There were even instances in which art was no longer confined to the gallery.

All the things by which the common man could say “that is art” suddenly were not in agreement with the gallery’s definition of art. Is it art on Pollock’s canvas, when he himself painted with no subject in mind? When Haans Hacke takes a printer1 and imbues it with a certain meaning, is it as easy for us to say that that is art? What about when Walter de Maria arranges lightning-rods2 in the middle of the desert, as to make art out of the lightning between them? Is that art?

Not even the element of education, connection to the artist, or uniqueness survived either. With the advent of pop art, Warhol began to create works specifically designed for mass consumption using mass production techniques. Warhol sought not to prove himself in the realm of meaning as other painters had long did, but rather instead embrace the simplicity of taste and produce things devoid of meaning, slappable on a t-shirt, on a wall, anywhere. And when you purchased a Warhol, there was no guarantee you’d even be purchasing something by him, as his works were rapid-fire and mass-produced by an assembly line’s worth of people.

In our modern era, it has gotten to the point where we’re so accustomed to this pushing of limits that Jeff Koons can pass off a simple balloon dog as high art and it’s accepted.

The notion of such things being art have long offended and sparked debate. It’s easy to see why, as they completely problematize the formal foundations we’ve come to rely on. How do we tell art without the subject, without the gallery, without the paintbrush, without the artist himself?

1. The Traditionalist Answer

Taking it a step further, what even is art? For the traditionalist, this question is easy to answer: true art is Michelangelo’s David. It’s either an immaculate painting or a fine marble statue, and no amount of modernist perversion changes that. What is the conservative argument against Pollock? “Just look at it.” This is unsurprising, as conservative epistemology has long relied on simplicity and common-sense intuition. This is not a bug, but a feature, as it acts as a bulwark against the ability for more abstract and theoretical foundations to obfuscate complete BS.

After all, this isn’t rocket science, this is aesthetics: the study of beauty. Why should we look down on the common man’s ability to instinctually discern it? What makes an ability to recognize good art any more exclusive than say, an ability to recognize good cooking? Sure, food critics exist just as art critics do, but everyone else has taste buds too. The old trope of this special taste of “the meals prepared back home” came not from critics but commoners.

It’s a rather simple and sensible answer, and one which was taken for granted for the bulk of history. But with the advent of the modern era, this was no longer possible. Not because of modernist ideology or any such change in social values, but rather instead something much more fundamental: industrialization.

The Industrial Revolution brought with it some key social changes which would inadverdently impact popular aesthetics:

- Urbanization, and with it the displacement of a previously rural population into an alien and isolated environment

- Mass-production techniques, and with it the rise of a consumer society dominated by the middle-class

- The decline of the old aristocracy, and the rise of the aforementioned middle-classes

The combination of all of these things gave rise to a new artistic phenomenon known as “kitsch”:

Kitsch, using for raw material the debased and academicized simulacra of genuine culture, welcomes and cultivates this insensibility. It is the source of its profits. Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas. Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations. Kitsch changes according to style, but remains always the same. Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money — not even their time. The precondition for kitsch, a condition without which kitsch would be impossible, is the availability close at hand of a fully matured cultural tradition, whose discoveries, acquisitions, and perfected self-consciousness kitsch can take advantage of for its own ends. It borrows from it devices, tricks, stratagems, rules of thumb, themes, converts them into a system, and discards the rest. It draws its life blood, so to speak, from this reservoir of accumulated experience. This is what is really meant when it is said that the popular art and literature of today were once the daring, esoteric art and literature of yesterday.

Kitsch is best defined as artistic simulacra, it is that which attempts to act as a “shortcut” to the social relations surrounding art. The actual artistic content itself is secondary, what matters is everything else we associate with art except the art itself.

What do I mean by “social relations surrounding art”? I refer to all the “functional” aspects of art. Art as a way to signal prestige or culturedness, art as an attempt to reclaim authenticity, art as a political or moral statement, etc.

Kitsch is distinctly industrial in that these feelings/relations it tries to invoke is done so in a standardized way, according to formulas and sold as generically as possible. No longer was art commissioned by any one king or noble with his peculiar tastes, but rather instead consumed by a general middle class with broad appeal in mind. It parasitically adopts the style of established traditions not for any of their inherent properties but for the intellectual vogue it’s able to signal.

The same Academic techniques which were employed by the masters of the 18th century were now being mass-replicated into countless nameless, generic paintings born less out of individual vision and more out of market demand.

It is through repetition that which originally provoked such an intense emotional reaction loses both its meaning and emotional intensity. This sort of traditionally envisioned, sublime encounter we have with a great work of art ceases to be possible when it loses both its uniqueness and specificity.

When we have Hall of the Mountain King being played in cartoons or Frankenstein showing up in Halloween advertising, we regard these things as cliche? Why? Is it because of something inherent in their original substance? Of course not, both of these held a genuine sway when the public first encountered them. It’s cliche because of the continued process of repetition: such things begin to detach themselves from their context and become fundamentally generic.

Reduced to the generic, such works can only signal certain concepts. Thomas Kinkade painting a bucolic landscape can give us an idea of how we’re supposed to respond to it: we can see that it signals the good old days, some sort of bucolic authenticity, etc.

But does it actually genuinely, primordially evoke that in us, or does it simply signal “oh, I am supposed to respond this way”. Is there anything even particularly distinct or inspired about Kinkade’s work that separates it from what I’d find on a puzzlebox? The fact that I can find something functionally identical on any mug, any puzzlebox, or any children’s book speaks to that character of repetition again. It also explains why I have zero emotional response: when I see this I don’t see the painting itself. What I see is the function such class of paintings are meant to serve in our society and all the objects it is associated with.

The middle classes who flocked to these paintings were less interested in genuine encounter with the painting as much as filling the house with another prop. Why do such a thing? Because it signals to others something about you.

Kinkade marketed his paintings as being emblematic of traditional Christian values and as a return to “true art” from all the modernist experimentation. Those who bought in were also often evangelical Christians, viewing their purchase of such a commodity as proof of adherence to these values. Never mind the fact that you could literally walk into a Thomas Kinkade store at your local shopping mall, by having this in your house, you were telling both your guests and yourself what kind of person you are.

My Marxist readers may notice this is quite literally the definition of spectacle, social relations being mediated by commodities via the medium of imagery.

And this is where we have to turn our critiques back on the traditionalists: the charge has long been that kitsch is fundamentally reactionary. I would like to posit the reverse: reactionary ideology is fundamentally kitsch.

We can see this even in more explicitly right-wing projects such as the Christ the King statue in Świebodzin, Poland. The effort was spearheaded by the Polish Catholic Church and an ultranationalist organization which proclaimed the Poles to be God’s true chosen people.

It is incredibly gaudy, one could even argue masturbatory, but what makes it so? It’s because its elements signal something not present within the work itself but within the tradition it parasitically imitates.

The religious subject, focus on size, and usage of gold and white all derive their meaning purely from cultural notions of “traditional and proper art”, which has its roots not in the aesthetic but rather instead in the historical. The ancient statues which come to mind when looking at this come to mind because of their historical connotation. They are said to be beautiful, not because of what they are in and of themselves.

After all, if this was something intrinsic, we would not see the obsession with replicating the “white marble” form, which is in reality the product of historical accident3 rather than artistic intent.

Rather instead, I believe it makes more sense to consider the admiration of ancient statues as coming not from the statues but rather instead the ancient-ness. Their value comes from the ability to peddle the age-old nationalist myth of some great lost ancient civilization the “true people” are heirs to and must return towards.

It’s beautiful not because it is, but rather instead because it must be. It must be beautiful because this “Atlantis” we strive towards is where our dreams will be realized. And we see its purpose is just as hollow as its heritage: it’s merely instrumental towards the larger nation-building project Poland has been undertaking in recent years.

Would such a statue really be any functionally different if it was a statue of Mao? Placed in the middle of China? If its composition was the exact same, just with a different subject?

Is it so unbelievable? After all, as Zizek points out, this same sort of sublime aesthetic beauty has in fact been adopted in such contradictory ways, such as with Beethoven’s 9th Symphony:

What does this famous Ode to Joy stand for? It’s usually perceived as a kind of ode to humanity as such to the brotherhood and freedom of all people. And what strikes the eye here is the universal adaptability of this well-known melody. It can be used by political movements which are totally opposed to each other. In Nazi Germany it was widely used to celebrate great public events. In Soviet Union, Beethoven was lionised and the Ode to Joy was performed almost as a kind of communist song. In China during the time of the great Cultural Revolution when almost all of western music was prohibited, the 9th symphony was accepted. It was allowed to play it as a piece of progressive bourgeois music. At the extreme right in South Rhodesia before it became Zimbabwe, it proclaimed independence to be able to postpone the abolishment of apartheid. There, for those couple of years of independence of Rhodesia again, the melody of Ode to Joy, with changed lyrics of course, was the anthem of the country. At the opposite end when Abimael Guzman President Gonzalo, the leader of Sendero Luminoso, the Shining Path, the extreme leftist guerrilla in Peru. When he was asked by a journalist which piece of music was his favourite he claimed, again Beethoven’s 9th symphony Ode to Joy. When Germany was still divided and their team was appearing together at the Olympics, when one of the Germans won golden medal, again Old to Joy was played instead of either East or West German national anthem. And even now today Ode to Joy is the unofficial anthem of European union.

What the evangelical hero Kinkade and the Poles have in common is that their preoccupation is formal. Their focus is stylistic: reflected in their attempts to recreate and analyze the old tradition, we see they conceive of art as an ensemble of motifs.

And it’s through this lens we can come to understand why a painter such as Norman Rockwell so captures the conservative imagination. When you look at a Rockwell painting, what is the first thing that comes to mind?

1950s America and all of its associated motifs. Family, order, sentimentality, patriotism. Republican Newt Gingrich would make it a point to speak of his family in “Rockwellian” terms, presumably to associate his own politics with such motifs.

But here is the interesting thing. Rockwell himself was famously apolitical. He regarded any attempt to discern his politics as a sign that he had “failed as a professional”4. Keep in mind that while nostalgia can now be seen as a motif of Rockwell paintings, he was originally painting for an audience living in the exact same era. This is why for every family dinner5 you see him paint, you also see allusions to civil rights6.

So, then why does it capture the traditional imagination as so? Well, it has to do with that fact of the 1950s. All these things Rockwell took to portraying in the world around him came to accidentally create a collection of period pieces. The feelings of nostalgia evoked here are no more profound or intentional than that evoked by old MTV commercials.

What characteristic about Rockwell’s work which makes this possible is its aforementioned “apoliticality”. There’s a reason why the Four Freedoms is remembered and not Murder in Mississippi7.

(The interesting thing about the latter is that he admits that painting it in his usual style as opposed to the early, impressionistic sketches “removed the anger” from it. Any Rockwellian-ness is missing from the pure sketch.)

Four Freedoms is an interesting case in that while it is an explicit reference to FDR, it is on national as opposed to “political” grounds.

What I mean by this is that what is evoked in these images is the dominant ideology of “American-ness”. What is expressed in these paintings is perfectly in line with the conservatism and liberalism of its time, and arguably even today. There is nothing in Rockwell’s paintings that say, Kennedy or Nixon would find offensive. If anything, this is compounded by the fact that he had painted countless presidents who were often on opposite ends of the spectrum. What bound him to both Nixon and LBJ was that he was neither a “liberal” nor a “conservative” painter, but “America’s painter”.

Yet, this neutrality is a false one. What we still see invoked is this idea of a “true America” as implicit. Yet, as someone published on calendars, advertisements, and magazines what this means always has to be left intentionally vague as so it is up to the viewer to fill in the blanks with what they desire.

Once again, returning to Zizek’s analysis of Ode to Joy:

So it’s truly that we can imagine a kind of a perverse scene of universal fraternity where Osama Bin Laden is embracing President Bush, Saddam is embracing Fidel Castro, white races is embracing Mao Tse Tung and all together they sing Ode to Joy. It works, and this is how every ideology has to work. It’s never just meaning. It always also has to work as an empty container open to all possible meanings. It’s, you know, that gut feeling that we feel when we experience something pathetic and we say: ‘Oh my God, I am so moved, there is something so deep.’ But you never know what this depth is. It’s a void.

Zizek uses this in order to critique ideology, by considering the ways in which such a work, even one with such an important legacy as Ode to Joy, is used.

It also gives us something else to consider about art: when we look at the sort of cultural significance or “meaning” in something such as Ode to Joy, ancient Greco-Roman statues, or any Rockwell painting, it’s not enough for us to consider solely the artist’s intent: reception absolutely plays a role.

The meaning projected onto them now, looking back, is quite removed from their original intent, but what we see instead is that functionally, in society, how these images are shared, internalized, and communicated ultimately govern their social function. And if everyone treats a work one way, organizes their vision of society around it being retrofitted into a certain political framework, etc., is that not functionally the same as a “legitimate” interpretation?

The key word there is “now”: the irony is that propaganda has the capacity to take these “traditional” images and bestowed upon them a contemporary character, irrespective of their origins.

Capitalism (and arguably industrial society as a whole) is built upon mass, standardized production, and this applies to the production of images too. The notion that we can flatten something as broad as “ancient European art” and flatten something so varied into a singular aesthetic, the way in which these images can be delivered to as broad an audience as possible (by being as vague as possible), yet still as personally felt as possible (at least in how the individual consumer relates to these messages). Once again, this is very much restating the Situationist theory of spectacle.

But the important thing to note here is that nostalgia is also a vicarious emotion, able to be preyed upon like anything else. Of course these images are being perpetually reproduced (and thus always contemporary), and as a result can only ever be a simulacra. Nobody alive today lived in Ancient Athens, very few remember the World War II of Rockwell, etc.

Even supposedly de-historicized examples of “beautiful art”, such as Beethoven’s Ode to Joy or Kinkade’s fantasy landscapes still find themselves thrust into the contemporary world through association. All the better they don’t have a pre-existing history to get in the way. I’m sure Beethoven did not conceive of his magnum opus being played as a rallying cry for every political movement under the sun.

So really, all this does is just leave us with more questions.

2. Is There An Answer?

Can we even speak about a “meaning” to art?

It’s a question worth asking in an era such as our own, where we’ve already seen the extent of post-modern art, and one in which we are waging debates over the validity of artistic works generated by AI.

We are no longer dealing with the old world of enchantment and ideals, but rather instead one whose outlook is a lot more cynical and therapeutic.

A question as fundamental as this does require us to consider the basics first.

It is a basic fact that any work of art is both created and seen (or experienced via whichever sense is suited to the medium, to be more accurate).

Another basic fact is that the actual, physical content itself is objective. When I look at the Mona Lisa, I’m looking at the same shapes, colors, and brushstrokes as you are. It’s not as if you can somehow percieve your way into the painting having a circular frame.

The objectivity of content acts as an anchor of sorts. Yes, you can say even despite this “meaning” and “intent” are intangible terms, but these ideas do not exist on some sort of separate metaphysical plane from the work itself. When I ask myself what the Mona Lisa “is about”, I’m implicitly referring to something and you recognize that thing I am referring to.

Implicit within the question is the tether to objectivity. That painting originated from somewhere, whether we understand it as the mind of the artist or the cultural fabric of its context (as Barthes would argue). Before we can even begin to interpret it, we have to first look at it, which inevitably is going to put a bound on what we’re willing to glean from it.

Rockwell’s paintings were only capable of taking on such a contemporary meaning precisely because within their objective content was a positive depiction of American life. The moments captured, the colors used, all of these are what ended up defining how it’d be responded to. Murder in Missisippi lacks either the subject or the colors, so it ends up not being interpreted in such a way.

Note that I said “not”, as opposed to “can’t”. The cynical, subjective view of art gives too much focus to possibilities, when what really matters is the function. Does it really matter if I theorycraft a way a work could possibly be taken or debate about whether or not there is a hypothetical person who could see it that way in good-faith?

Rather instead, if we’re going to take such an approach, we should take one which looks at how it is actually responded to, as it is those interpretations which actually bear relevance to public consciousness.

3. The Social Answer

I want to take a step and and answer the question in objective terms, putting aside these high-minded philosophic questions of aesthetics and beauty for a second. I want to simply ask — in a literal, functional sense — what does art do?

Thinking in such terms, and putting aside value judgements should allow us to narrow down the field of potential definitions. One of the biggest issues with these discussions is that many attempt to conflate the questions of “what is true art” and “what is good art”, but doing this only unnecessarily obfuscates things. One can draw a line in the sand on where art must stop, but it’s ultimately meaningless if left as a subjective value judgement completely detached from what the rest of the world is doing.

As discussed above, formal characteristics are insufficient alone as a basis for understanding art. With modern art, the canvas hasn’t remained, the subj ect hasn’t remained, but what has remained is still the gallery. There’s still tastemakers, high price tags, conventions, and a whole culture surrounding high art, just as there was 100 years ago.

Quite possibly the one defining trait we can give to art is that it appears to be useless. Even in the most ridiculous examples of modern art, such as Jeff Koons stacking two vacuum cleaners on top of each other8, we can still see the uselessness present within its situation.

The vacuum cleaners are placed within a glass box, away from touching. If you were to try and start using the vacuums to clean up your house, you’d likely get scolded by Koons for “ruining the work”. Why is that though? Probably because if we were to interact with it, it would return to the realm of object and we’d realize there’s really nothing separating this from the countless other cleaners of the same model once produced.

Are we at the point where we could take a toothbrush, stick it on a pedestal, and call it a work of art? Probably. But you can’t call my toothbrush a work of art. Why is that? Because of how I interact with it. I’m constantly sticking it in my mouth, I’m constantly interacting with it as a tool, something which serves a definite, clearly defined purpose towards some end. How is this gonna go in a gallery or be critiqued when I need it every day in my bathroom? What, is every single patron going to share the experience of using the same brush? Then it’d cease to serve the function of an ordinary toothbrush.

Really, it’s the designated spot as opposed to the work itself which really is where the definition is contained. Every work of art has a gallery, if not that, then a wall.

We see this definition holds up against even spatial edge cases. When Gordon-Matta Clark cuts holes in ruined buildings9, we still recognize it as art, even if it’s not contained within a gallery. But even if it’s not contained within a gallery-proper, the social rules of the gallery still apply.

Formally, this work is no different from any regular abandoned building (characteristic of social waste), nor is it necessarily experientially. As Zizek points out10, one can find in interacting with waste a powerful emotional and creative experience.

It is socially where we see the difference. In this hypothetical regular ruined building, it’s not much of a deal if I trespass. It’s not a big deal if I squat there, because the building is essentially waste. In a Matta-Clark building this is not the case. The Matta-Clark building is meant to be looked at, appreciated with a certain level of distance. It is in this, we must return to this idea that the uselessness of art is apparent.

Something truly useless, such as an abandoned building, allows full freedom of interaction, as there is no defined way to interact with it. There are no rules, as rules are always oriented towards some end. There are no boundaries, as in a society which is hyper-functional, its belongs nowhere. It’s very existence is an infringement upon boundaries, so to step into it is to step into unknown territory. It is in such a space, unbounded by definition that the mind is able to roam and reflect upon itself. Purpose can be seen as symbolic of the objective world and its constraints, whereas its absence leaves the subjective alone, in a state of alterity.

Even in interpretation, we lose a bit of freedom when we have to consider the intent of Matta-Clark. The giant holes hang there as an elephant in the room, influencing whatever meaning we are to discern from it. This is usually where the critics pour in, piecing together their contextual clues to decode the piece as if it is a puzzle. They’ll speak of emptiness of urban life, decay, and so on, these are all still presuppositions which shape how we are supposed to relate to it.

But then that means that any work of art which totally embraces this freedom is functionally no different from trash. This definition does a proper job of describing how art actually functions on a social level, but makes no statements on quality, meaning, or aesthetic value.

4. Art as Communication

Perhaps the aim of art is to recreate this freedom not in an accidental but rather instead a purposeful fashion, to make it relevant. To capture that otherworldly moment and direct it back to Earth. To take that moment of aesthetic contemplation and render it communicable, to take subjective reflection and turn that into a subjective response to the objective world.

In medieval art, we see memento mori, a constant reminder of the limits objective realities (death being the supreme example) place on us. In it we see how art communicates religious truths, with the art adorning Cathedrals often acting as a way of conveying the Gospel to the illiterate masses. We see mythical elements employed as emblematic of an enchanted world, in which both the fear and wonder of the Unknown struck a population which lacked full scientific knowledge.

For the Academic artists, their works were characteristic of the Enlightenment philosophy: a supreme confidence in the total coherence between our rational minds and a perfect, orderly world. We see this communicate the mission of striving towards an objective ideal.

For the Expressionists, we saw this question answered yet again, but this time differently. The objective world is viewed as a constraint in its finitude, shackles upon an infinite mind. Art here is seen as a protest against the restraints of externality, a demand for total freedom of the mind, expressing that which is ordinary incommunicable.

This is possible because the canvas is where the mind meets the hands, and the theoretical limitlessness of the imagination is continuously at struggle with the actual limitations of life in general. After all, even the most otherworldly of art is still made by an artist who exists in this world.

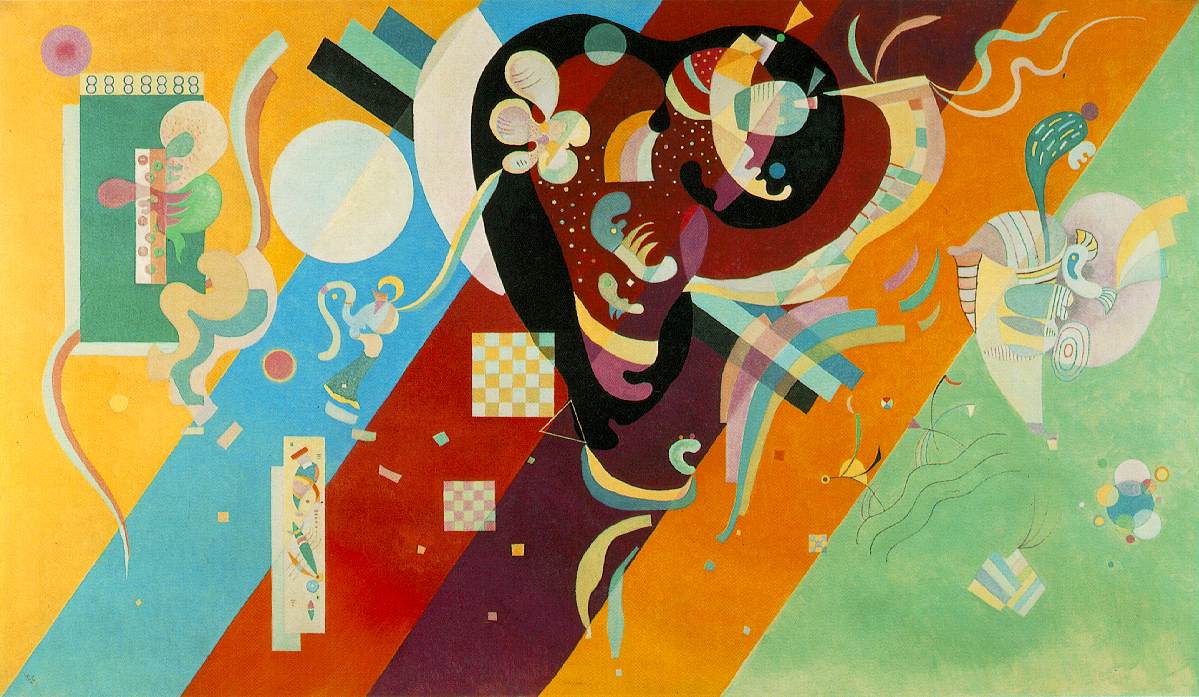

On the existential level, we see this manifest most brilliantly (in my view at least) with Wassily Kandinsky. He does away with the concept of subject, instead contemplating art in its most basic forms. A line, a shape, a color, he concieves of all of these not just as a reflection on the formal, but rather instead the spiritual. He recognizes that link between the mind and the canvas, and taps into it to try and overcome his limitation: namely the inability of the soul to express itself in concrete terms.

And what we see is that his work takes upon a strangely musical quality, despite being a simple painting. Staring into it, one contemplates not just the mortality of their physical shell and the world of objects surrounding it, but also feels a level of resonance with all that from within which cannot be expressed with words.

This struggle is not just limited to the existential, however. Just as our limitations are not just merely mortal but social, so are the ways in which art can communicate. In other words, art need not make a philosophic statement to be meaningful but can also instead speak to that which is concretely in one’s own environment.

Take something such as graffiti: graffiti stands outside of the world of high art, yet in reality it comes closer to that elusive freedom than anything Pollock could create.

Graffiti was borne out of the conditions of urban living, and entirely speaks to the conditions of it11. Not in some abstract, planned out, metaphorical sense, but rather instead spontaneously and organically. The messages and imagery plastered on the side of a subway or building are both by and for those who occupy this street-space.

And we see the ways in which this can transform the environment itself. Abandoned buildings are given new character, the boundaries and property subdivisions break down with their violation, and that aforementioned authentic experience with waste comes to the forefront.

In the latter 20th-century, when graffiti really took off, it also happened to be a time with many cities in decay. Graffiti treats the entire city itself as waste, and this step-back in perspective challenges the social organization of space in urban environments. It acts as a demand for freedom against the byzantine restraints and boundaries that define daily life in an urban setting. The limitation here on freedom is not existential, as Kandinsky had to deal with, but rather instead environmental and social (see Lefebvre12). Still very much real and relevant.

That’s why within graffiti, you see a mixture of work created for aesthetic reasons and more explicitly political messages, neither one fully defining what graffiti is. The breaking of boundaries has rescued it from the social separation high-art was long confined to, and placed it into the midst of the real world, not in galleries but on the same streets one walks to the store or work.

We see this extend into the digital age, with the way in which early online networks made use of computers’ ability to freely manipulate information in order to create a “remix culture”. The mass-media which was vertically delivered in the 20th century through CDs and TV now was at the hands of the average citizen. Not just to consume or pirate, but also modify and create new ideas using the existing intellectual properties as a foundation.

In this overlap between the culture of torrenting and remixing, we see serious challenges to intellectual property as a concept, and the strict consumer/producer division. People were taking what they were consuming, that had been alien to them before, or even cultural artifacts which were wasteful/outdated (as was the case in B-Games and vaporwave), and using it as a way to realize their own agency as a creative subject.

For the majority of its lifespan, the television has long been symbolic of a creative dead-end, a crystallization of the unfreedom of media consumption. Images come and go rapidly, but hold no room for reflection or creative reflection.

Once again we see a social challenge not baked into some intentional message, but rather instead implicit and organically realized through the process of production. Yet again we see a barrier broken, as the message isn’t simply conveyed or told, but realized in the action itself.

So, we’ve seen the ways in which art can act as a mediator in the struggle between the Mind and Reality or between the Individual and Society, but these are all only specific applications. We still haven’t gotten to the essence of art itself.

Art is fundamentally a form of communication between the Artist and their Audience. This is a rather trite statement on its own, but the key thing here is the bi-polarity. Both the artist and the audience are continuously negotiating the meaning of any one given work, but on common territory, namely the work itself.

We have many ways of communicating, such as words, but dialogue fundamentally exists to describe what is. Art, instead — through its indirectness and lack of concreteness — has the potential to describe what can be.

Plato famously wishes to return to “pure soul”, Kandinsky visualizes such an existence. The Situationists wished to do away with the boredom of everyday life, graffiti helped unravel the environment in which people’s every day lives were situated.

Is art as a whole an objective phenomenon, then? Yes.

Think of it almost as a transmission. The work is initially conceived from subjectivity, is drawn onto an objective canvas, where it is viewed with objective senses, before being internalized once again on a subjective level.

Does any work of art have an objective meaning then? Yes, but that meaning is the product of a continuous tug of war between the artist, who wants to express as much as possible, and the audience, who has a desire to digest it as accessibly as possible. It’s the intersection between conception and reception, which can only converge on one point. The work itself.

The brushstrokes, the depictions, the color, these basic forms are what could be most accurately said to contain the true meaning of art.

Footnotes

- https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/2008.232/ ↩︎

- https://www.diaart.org/visit/visit-our-locations-sites/walter-de-maria-the-lightning-field ↩︎

- https://edu.rsc.org/resources/were-ancient-greek-statues-white-or-coloured/1639.article ↩︎

- https://outfront.blogs.cnn.com/2012/02/28/was-norman-rockwell-a-republican/ ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_from_Want ↩︎

- https://www.nrm.org/MT/text/NewKidsNeighborhood.html ↩︎

- https://www.nrm.org/2020/06/norman-rockwell-murder-in-mississippi/ ↩︎

- https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81090 ↩︎

- https://publicdelivery.org/matta-clark-conical-intersect/ ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5nT_po2E-kA ↩︎

- https://journals.openedition.org/eue/1421 ↩︎

- https://journals.openedition.org/eue/1421 ↩︎

Blogger and software engineer. I write on tech, politics, and theology.