This is part two of a multi-part series analyzing the relationship between Christianity and work. Click here to begin at the introduction and also find the table of contents/bibliography.

The worst arguments tend to be over semantics, and unfortunately for us, there is a lot of semantic disagreement on how the word “work” is to be interpreted. It’s very easy to walk into a topic like this leaning on preconceptions, so our first task should be properly defining work, and distinguishing it from labour.

The line drawn between work and labour is generally ambiguous, so before we proceed we will have to reconcile this matter. For the purposes of this essay, labour is defined as any mental or physical activity conducted by a person onto an object as to either transform it into one of value (either use-value or exchange-value could apply here, depending on the context) or add to its value. As for the definition of work, we will have to take a more thorough investigation:

(For the purposes of this essay, I will be considering work as a historically-specific activity peculiar to industrial-capitalist society. Obviously, toil has long existed outside of this context, but what is going to be apparent throughout the course of my argument is that it takes upon a unique character within the currently existing economic framework. Considering work as an unchanging activity across all time periods without distinction would end up neglecting how it has fundamentally evolved alongside human civilization.)

2.1. Work as Compulsory

The traditional understanding of work stresses that it is compulsory, not just in an internal sense (such as an animal being compulsed to forage for food by the logic of its biology), but also in an external sense. This distinction means that an activity can be considered “labour” or “productive” without it necessarily being “work” per se.

My minimum definition of work is forced labour, that is, compulsory production. Both elements are essential. Work is production enforced by economic or political means, by the carrot or the stick. (The carrot is just the stick by other means.) But not all creation is work. Work is never done for its own sake, it’s done on account of some product or output that the worker (or, more often, somebody else) gets out of it. This is what work necessarily is. To define it is to despise it. But work is usually even worse than its definition decrees. The dynamic of domination intrinsic to work tends over time toward elaboration. In advanced work-riddled societies, including all industrial societies whether capitalist or communist, work invariably acquires other attributes which accentuate its obnoxiousness. (Black 1986, 6)

What exactly this external pressure looks like varies not just based on one’s interpretation but also the environment in which work is being employed. Some may interpret their work as part of a religious obligation. Certain readings of the Vedas have long been used to justify the Indian caste system. Even in Christianity, the concept of a “vocational calling” has been echoed by writers such as John Calvin.

The magistrate will execute his office with greater pleasure, the father of a family will confine himself to his duty with more satisfaction, and all, in their respective spheres of life, will bear and surmount the inconveniences, cares, disappointments, and anxieties which befall them, when they shall be persuaded that every individual has his burden laid upon him by God. Hence also will arise peculiar consolation, since there will be no employment so mean and sordid (provided we follow our vocation) as not to appear truly respectable, and be deemed highly important in the sight of God. (Calvin 1536, 870)

Divine commands aside, there also exist more objective forms of coercion. A country which employs slavery or work-camps, the work is being compelled by the state and the threat of physical retaliation to those who refuse. It could even be argued that the market in and of itself could compel people to perform activities which may not be directly linked to their survival.

First, the fact that labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature;that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home. His labor is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labor. It is therefore not the satisfaction of a need; it is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it. Its alien character emerges clearly in the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists, labor is shunned like the plague. (Marx 1844, 30)

Whether or not the compulsion in any of the above scenarios are justified or not is irrelevant to the point made, which is that work is a compulsory affair, the compulsion is external in nature, and that this compulsion dictates not just the existence of the worker but also the character of “work” itself.

On that note, although this characteristic may seem the most apparent, it fails to really shed much light on the matter. If this conception of work is something to be holistically “abolished” as Black proposes, then where is the line to be drawn?

If we define work as “external activity”, then social production entirely ceases to function with its abolition. I fail to see how “the commune needs me to produce this” is any less external than “the market needs me to produce this”. Your individual wants and needs are inevitably going to be tied to and shaped by social wants and needs. Severing that connection would be to turn every man into his own Robinson Crusoe, to put an end to civilization itself. Perhaps that’s an attractive outcome for some, but the implications of that aren’t something I see as worth entertaining in this essay.

If we wish to only abolish “coerced activity”, then we run the risk of reiterating the fundamental axioms of capitalist society. Freedom of contract already exists, meaning wage-slaves aren’t slaves in the conventional sense. Some socialists may object to this, arguing that this freedom is a farce because of the existence of private property, but that is completely besides the point. My work does not suddenly cease to become work now that I’m performing it at a co-operatively owned factory. So, there must be a deeper explanation.

It certainly doesn’t help that the space between “external activity” and “coerced activity” is nebulously defined. A debate over whether or not the invisible hand really forces people to work will inevitably devolve into one of semantics, obfuscating the true nature of the topic. Barking up another tree will prove more fruitful to our investigation.

2.2. Work as a Division of Labor

What I’d rather focus on instead is the essential characteristics of work as being comprised of a set of divisions.

Firstly, there’s the division of labor, a concept that has been known to us for centuries now. Even writers as old as Calvin and Smith provide extensive insight into this division. Calvin was interested in understanding what such division could mean to a Christian, whereas for Smith it was a question of the economic origins and implications of its existence.

“Division of labor” can interpreted in two ways, one is in the vocational sense which Calvin refers to. The second form is best described as the specialization of labor.

One man draws out the wire; another straights it; a third cuts it; a fourth points it; a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business; to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some factories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small factory of this kind, where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day…

But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day; that is, certainly, not the two hundred and fortieth, perhaps not the four thousand eight hundredth, part of what they are at present capable of performing, in consequence of a proper division and combination of their different operations. (Smith 1776, 8-9)

Using the example of a pin factory, Smith demonstrates the division of labour by associating each man with a task. Within the context of this larger factory, we see each man’s work as defined by a specialized task. Each of these tasks only play one part in the production of the pin. No matter how skilled a worker becomes at drawing out the wire, he alone cannot produce the pin. Just like a machine, his training refines his skills towards being able to only perform one specialized task incredibly well: this renders him dependent on the factory as a whole to render his labour useful. This only intensifies as the firm grows and each worker’s role in the production process becomes more and more narrow.

Unlike the vocational form, the effects industrialization had on this are much more pronounced. In medieval and early-modern societies, artisans would develop goods and tools by hand from start to finish, with a full understanding of the production process, control over the supply-chain, and distribution to market.

Yet beneath the similarities with the Old Regime there lurked a difference, for the seeming independence of artisans was built increasingly on a foundation of dependency. No longer did masters,or shopkeepers for that matter, have much control over access to their materials, now provided by merchant industrialists, factors, and wholesalers. Moreover, masters came to rely on a steady flow of orders,often from only a few middlemen or owners of factories. The same can be said of access to credit and to markets, which was increasingly controlled by merchant operations (Farr 2004).

Today, we have the assembly line. Rather than making it one person’s job to create a hammer, we have one person to cut the wood, one person to shape the handle, one person to dye the handle, and so on and so forth. This is of course a hypothetical, but point still stands, which is that man has become not just alienated from the product of his own labor, but also the process itself.

The artisans had an easier time finding a positive identity in their work because they still held a degree of autonomy over the production process, they still felt as if their labor was their own. This most likely explains the prevalence of artisan culture and the appeal of early “worker-ist” movements to predominantly this class.

Another key aspect of artisan identity, which existed alongside these status divisions, was the close relationship between production and retailing. Buying raw materials and selling one’s products were integral to artisan identity, and most Florentine guilds both manufactured and retailed their wares. Artisan identity always involved the sale of products in the local marketplace, though some artisans eventually moved into the ranks of the mercantile class. Artisans are often defined in opposition to merchants because of their ties to local rather than foreign markets and the cultural perception of their rootedness (often more imagined than real) in contrast to the merchants’ mobility. Yet precisely because the master craftsman’s identity was localized, dependent upon recognition by peers and neighbors, premodern artisans often imaginatively constructed their relations to the nation. In the fourteenth century, the brothers of the London Bowercraft censured the bowstrings of non-guild members, maintaining that “the greatest damage might easily ensue unto our Lord the King and his realm” through faulty products. The work of craftsmen, like that of knights, was cast as protecting the entire nation; through their collective identity, the bowers articulated a sense of national belonging. (Pappano 2013)

The same cannot be said for the proletarian, who in his work, is reduced to a mere machine, something subhuman.

Utter, unnatural deprivation, putrefied nature, comes to be his life-element. None of his senses exist any longer, and not only in its human fashion, but in an inhuman fashion, and therefore not even in an animal fashion…

The savage and the animal have at least the need to hunt, to roam, etc. – the need of companionship. The simplification of the machine, of labor is used to make a worker out of the human being still in the making, the completely immature human being, the child – whilst the worker has become a neglected child. The machine accommodates itself to the weakness of the human being in order to make the weak human being into a machine…

By reducing the worker’s need to the barest and most miserable level of physical subsistence,and by reducing his activity to the most abstract mechanical movement; thus he says: Man has no other need either of activity or of enjoyment. For he call this life, too, human life and existence.

By counting the most meager form of life (existence) as the standard, indeed, as the general standard – general because it is applicable to the mass of men. He changes the worker into an insensible being lacking all needs, just as he changes his activity into a pure abstraction from all activity. To him, therefore, every luxury of the worker seems to be reprehensible, and everything that goes beyond the most abstract need – be it in the realm of passive enjoyment, or a manifestation of activity – seems to him a luxury. (Marx 1844, 50-51)

While Smith focuses on the effects this has on total productive efficiency and the factory system as a whole, Marx analyses the same phenomena from the perspective of the individual worker:

The accumulation of capital increases the division of labor, and the division of labor increases the number of workers. Conversely, the number of workers increases the division of labor, just as the division of labor increases the accumulation of capital. With this division of labor on the one hand and the accumulation of capital on the other, the worker becomes ever more exclusively dependent on labor, and on a particular, very one-sided, machine-like labor at that. Just as he is thus depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine and from being a man becomes an abstract activity and a belly, so he also becomes ever more dependent on every fluctuation in market price, on the application of capital, and on the whim of the rich. Equally, the increase in the class of people wholly dependent on work intensifies competition among the workers, thus lowering their price. In the factory system this situation of the worker reaches its climax. (Marx 1844, 4)

The division of labour we see in this factory model is specific to the capitalist mode of production, and is magnitudes more intense than the vocational divisions to be found in pre-capitalist societies which still retained a concept of “work”. The stratification in our society is not just one of judges, doctors, and priests, but rather instead divided up by each step in the production process of a commodity. In addition, the increased efficiency and circular logic of capitalism ensures this fate remains a perpetual one.

2.3. Work as a Division of Activity

This not just only alienates the worker from his product as the socialist talking point goes, but also from the production-process itself. Man’s relationship to his labour is not merely a pragmatic one, but also an essentially existential one too, it is through labour that one is given the opportunity to assert their humanity:

For labor, life activity, productive life itself, appears to man in the first place merely as a means of satisfying a need – the need to maintain physical existence. Yet the productive life is the life of the species. It is life-engendering life. The whole character of a species, its species-character, is contained in the character of its life activity; and free, conscious activity is man’s species-character. Life itself appears only as a means to life.

The animal is immediately one with its life activity. It does not distinguish itself from it. It is its life activity. Man makes his life activity itself the object of his will and of his consciousness. He has conscious life activity. It is not a determination with which he directly merges. Conscious life activity distinguishes man immediately from animal life activity. It is just because of this that he is a species-being. Or it is only because he is a species-being that he is a conscious being, i.e., that his own life is an object for him. Only because of that is his activity free activity. Estranged labor reverses the relationship, so that it is just because man is a conscious being that he makes his life activity, his essential being, a mere means to his existence…

It is just in his work upon the objective world, therefore, that man really proves himself to be a species-being. This production is his active species-life. Through this production, nature appears as his work and his reality. The object of labor is, therefore, the objectification of man’s species-life: for he duplicates himself not only, as in consciousness, intellectually, but also actively, in reality, and therefore he sees himself in a world that he has created. In tearing away from man the object of his production, therefore, estranged labor tears from him his species-life, his real objectivity as a member of the species and transforms his advantage over animals into the disadvantage that his inorganic body, nature, is taken from him. (Marx 1844, 32)

This activity represents something more than just mere toil, it is the means by which one’s will can shape the world, the bridge between a person’s innermost passions and their immediate environment.

And the Lord God took the man Moses now adds, that the earth was given to man, with this condition, that he should occupy himself in its cultivation. Whence it follows that men were created to employ themselves in some work, and not to lie down in inactivity and idleness. This labor, truly, was pleasant, and full of delight, entirely exempt from all trouble and weariness; since however God ordained that man should be exercised in the culture of the ground, he condemned in his person, all indolent repose. Wherefore, nothing is more contrary to the order of nature, than to consume life in eating, drinking, and sleeping, while in the meantime we propose nothing to ourselves to do. (Calvin 1578, 77)

As made clear in the Genesis narrative, we were made in the likeness of the Creator, so it is only natural, that even despite our fallen state, we find purpose in the act of creation. But what separates this creation, this activity, from the daily routine of animals is the unity of mental and physical faculties. Our minds allow us to formulate an idea while our hands allow us to bring that idea to fruition. Marx’s conception of labor in its essential form attests to this.

(Secular readers may object that many animals have demonstrated intelligence, but this neglects that the Christian conception of humanity is an inherently dualist one: the body may be composed of carbon, but the soul is incorporeal. This can only imply an inherent distinction between man and the other creatures of the earth, one which cannot be understood in biological terms.)

Marx sees in Hegel’s account the bourgeois division of labour into physical and mental activities. In Marx’s view human beings are born not only with nutritive capabilities, but with mental ones that are inseparable from them. Human beings engage in their own process of reproduction with both material and mental capabilities united as a whole. (Uchida 1988, 9-10)

However, we do not live in Eden. The world we live in — its institutions, its social relations — has always been a corruption of God’s ideal, realized not just on the individual but also the structural level. We see this apply to work too: capitalism completely fractures its unity, so thoroughly separating the physical and mental components that any element of passion or will is to be drained. Unable to realize this unity individually, both the workers and the capitalists must interface through the value-form, which demands all labor, whether physical or mental, be entirely devoted towards its own reproduction. How can we argue that we are working to God’s glory when Caesar demands control over the spirit?

This claim can be challenged in one of two ways: either God does not care for the specifics of our work or that industrial society has not actually alienated labor.

In considering production in general Marx takes the human mind and body to be naturally united. This unity is broken by the capitalist division of labour in which the capitalist appears as mental labourer and the wage-worker as physical labourer. The capitalist orders the worker to labour in material production. Capital itself necessitates and posits a specific person, the capitalist, who mediates it. The capitalist has a mission to measure capital-value, which has to be maintained and increased in prospect during production. The capitalist’s mental activity continues in the process of circulation which actualises this possibility. Capital is personified in the capitalist, who internalises its value in capitalist consciousness. (Uchida 1988, 13)

Activity is also divided along lines of production and consumption, each commanding its own distinct sphere. Intuition tells us that this relationship is one-way: that consumption is like a pit which we fill up with the goods we produce. Production creates, consumption destroys, so the logic goes. Socialists often internalized this mentality, valorizing the proletariat as a class of production as opposed to petite-bourgeois consumerism. This perspective is the perspective of capital, which is unable to see activity the way the individual does.

Because Adam Smith studies capital from the viewpoint of the circuit of productive capital, he believes that the movement of capital starts from production. Therefore, with respect to the relation of production to consumption, he considers individual consumption as an act apart from production, and he does not take it up in relation to production. He thinks that individual consumption is unproductive and should be restrained in order to increase capital-stock, which is to be invested as capital in production. He merely affirms consumption when it is productive, and he emphasises parsimony as a subjective fact in capitalist accumulation. Though he asserts that the purpose of production is individual consumption, in fact he theorises production for the sake of production.

However, is individual consumption always unproductive? The individual returns to the process of production afterwards, not only with physical abilities reproduced, but with some knowledge of production and a revitalised morale. The political economist omits the subjective aspect of reproduction, which is typically shown to move from consumption back to production. But why does the political economist abstract from the subjective factor? This is because production is considered from the capitalist standpoint, so in this way any funds to reproduce the lives of workers appear as costs to be reduced. The subjective factor belongs to and is monopolised by the capitalist. (Uchida 1988, 14-15)

Just as the artist draws on previous influences, consumption is to be understood as a source of inspiration for future creation. This process is reciprocal and essential for the individual to be able to find meaning in their own activity through a process of continuous inspiration and re-appraisal against their own needs, aesthetic sensibilities, and virtues.

If we can speak of art as an industry, a job, and a commodity, whose to say we cannot reverse the logic? Is engineering not in and of itself creative? Whenever we look at an emerging industry, whether it be aviation or mobile phone technology, we see an incredibly wide array of designs and concepts. These periods are often referred to as the “wild west” in that there is no clear direction or standard, forcing engineers to exercise a large amount of creativity in their creations and where they draw inspiration from.

Given his close observance and use of nature as a foundation for many of his ideas, emulating natural flight was an obvious place to begin. Most of Leonardo’s aeronautical designs were ornithopters, machines that employed flapping wings to generate both lift and propulsion. He sketched such flying machines with the pilot prone, standing vertically, using arms, using legs. He drew detailed sketches of flapping wing mechanisms and means for actuating them. Imaginative as these designs were, the fundamental barrier to an ornithopter is the demonstrably limited muscle power and endurance of humans compared to birds. Leonardo could never have overcome this basic fact of human physiology…

In less than 20 pages of notes and drawings, the Codex on the Flight of Birds outlines a number of observations and beginning concepts that would find a place in the development of a successful airplane in the early twentieth century. Leonardo never abandoned his preoccupation with flapping wing designs, and did not develop the insights he recorded in the Codex on the Flight of Birds in any practical way. Nonetheless, centuries before any real progress toward a practical flying machine was achieved, the seeds of the ideas that would lead to humans spreading their wings germinated in the mind of da Vinci. In aeronautics, as with so many of the subjects he studied, he strode where no one had before. Leonardo lived a fifteenth century life, but a vision of the modern world spread before his mind’s eye. (Jakab 2013)

The artisan and the factory worker may produce the same thing, yet one finds much more meaning in his activity than the other. Why is that? To answer that question we have to ask ourselves: why do we work? If you were to bring the factory worker something he produced, would he be able to identify it? Or have those hours become a blur, just like the rest of his life? Would he be able to remember what he was thinking when he made it or how it affected him? Does the commodity in and of itself tell us anything about its production or the person who made it?

When we perform the same basic activity for multiple hours a day, every day, engulfed within the larger mass of the assembly line, how does it affect our development and psyche? What challenge does it provide, what opportunity does it provide for us to grow? Maintaining a routine, learning to become numb to drudgery and fatigue, and performing tasks without question or emotional hesitance are all things we expect out of our machines. What makes a man then, if he can never measure up to the machine he’s competing with?

If we can’t come up with a satisfactory explanation to any of these questions, if we remain entirely ignorant as to what we’re really doing or why our lives are structured in such a way, how can we confidently say that we’re doing a good job, that what we’re doing is to the glory of God?

Perhaps that’s why we can only conceive external justifications, it’s easier to just assume work can only ever be this way. Perhaps we can say that there’s more to life than work, but this ignores the importance of activity to the life-process. God gave us hands for a reason, after all.

When faced with this question of why, we often avoid the subject by resorting to cliches: we do what we do because “that’s how society functions”, or because “we have do do something”. These may be catchy and broadly acceptable, but they do not actually provide a meaningful answer to the matter at hand.

As a society, we betray our impoverished work ethic by our slogans. On a recent car trip I was passed by a truck with the following jingle painted on the back: “I owe, I owe, so off to work I go.” Here, in rather crude form, is a dominant work ethic today. It views work in mercenary terms – the thing that makes our acquisitive lifestyle possible. (Ryken 1987, 12)

These cliches mask the larger truth, which is that under a system of wage-labor, what we’re inherently working towards is going to be the wage. What else is there to look towards? The result, the reward, is what takes logical precedence and this is not a matter of personal interpretation. No amount of “social obligation” will change the fact that if you stop paying an employee, they’ll stop working whether by choice or by starvation.

Nowhere is this more clear than in Soviet society, which put a great deal of effort into manufacturing a cultural work-ethic without necessarily changing the nature of work itself.

Soviet “cavalier attitudes toward work” entered the political discourse as a never-ending problem and the popular culture as a constant joke.2 Some of those jokes about the notorious Soviet work ethic are still told today, most famously: “we pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.”…

Late Soviet society was famous for its presumably nonexistent work attitude across all occupations. Blue-collar workers got drunk during their shifts, collective farmers seldom showed up, students amused themselves instead of studying, and white-collar workers were rarely present in their offices. Employees working in the Soviet administration were everywhere but at their desks. (Oberländer 2017)

Is this because of some sort of immorally lazy tendency in people or a lack of emphasis on hard work in cultural values? Not likely:

Soviet scholars and party members did not always see the situation in this light. Instead they usually detected a low work morale that troubled them—especially considering that the generation now working had been entirely raised under Soviet socialism yet seemed to lack essential features of the new Soviet person. If people did not work, it indicated a lack of a proper socialist attitude toward work. The dubious Soviet work ethic was regarded, first and foremost, as a moral problem: accordingly, complaints and measures were aimed at working people themselves. Instruments to improve work discipline were introduced on an almost yearly basis across the country or at individual enterprises. If the moral education (vospitanie) provided by trade union members or factory sociologists did not help, compulsion exercised by comrades’ courts were used to try to discipline the workers…

While the Soviet literature was mostly preoccupied with immorality, the Western perspective usually stressed the lack of incentives as a reason why people did not work. (Oberländer 2017)

When we consider the work itself rather than the workers, the pieces begin to fall into place. We see that Soviet and Western society actually held very similar attitudes to the nature of work:

The Soviet Union built its existence on more than one paradox. One of its numerous contradictions is that the workers’ state cherished work as the means that made men into men and thus endorsed the biblical notion that those who do not work shall not eat. At the same time, the USSR claimed communism as its goal and therefore strove to extend nonworking time, based on the Marxist notion that the wealth of nations consisted in free time. As opposed to the biblical notion, work in the Marxist sense was less a moral condition of people who through work realized themselves than a price to be paid to gain as much free time as possible. Self-realization was supposed to happen in one’s free time, by and through the activities conducted in that portion of the day…

Although the two positions seem to be different at first glance, they share some commonalities. Both take for granted the lack of a positive attitude toward work. Both put forward a moral explanation, even though the Western perspective is only implicitly a statement about morality. Soviet observers detected a lack of socialist morality proper, while Western economists detected a general humanitarian problem: If people are not rewarded, they will not work. (Oberländer 2017)

The Soviet economic institutions, being far less robust and prone to abuse than the Western ones, did actually provide us with the opportunity to observe something revealing. The people did work, but they did so outside of the official firms:

The peculiarities of the Soviet planned economy need to be taken into consideration if we are to understand what “work” meant in the Soviet Union. Work in the sense of the eight-hour workday as gainful employment was not necessarily the primary means to provide for oneself or one’s family. Instead, in a society where many things could not be bought with money but had to be obtained through unofficial channels, the sphere of leisure gained importance for material production. Consequently, leisure was not necessarily a sphere for recreation and rest but rather a busy time governed by tight schedules. Gainful employment, in contrast, seemed to provide better possibilities for recreation and relaxation than so-called free time. This article hopes to expand notions of work by highlighting the many spheres in which Soviet people did work—be it in the official or the shadow economy, during official work time or beyond. In this sense, the spheres of work and leisure overlapped, and to a certain degree even changed places…

Last but not least, some workers in the Soviet Union used a considerable amount of their working time to work for themselves. They crafted material provided by their enterprises into something useful for their homes or garden plots. One female worker used to clean her pans and pots at her factory—during official work time, of course. Chaffeurs used the time spent waiting for their bosses to deliver certain items from A to B. Dacha owners, for example, hired a state-employed driver to transport stolen wood in a state-owned car to their dachas during the chauffeur’s official work time. In the first case, workers produced a useful thing for their own direct consumption; in the second, they sometimes earned money and more often engaged in useful networks known as blat. Whatever the reason for engaging in such forms of informal economic practices, it cannot be argued that those people did not work. (Oberländer 2017)

From all this we can conclude that people do have a natural inclination towards activity: one that blurs the lines between work and leisure, defying the rigid structure of the eight-hour day. It may not be work-proper, but it is undeniably productive.

2.4. Work as a Division of Time

However, the characteristic of work that has yielded the most discussion is its constitution of a division of time. When we talk about work in relation to time, we counterpose it against leisure, forming a dialectical relationship between the two. While this overlaps with the previous division, the uniquely temporal element here makes it warrant further discussion.

The quickest way to illustrate such a division is to allude to the very first division as a metaphor of sorts:

It was proper that the light, by means of which the world was to be adorned with such excellent beauty, should be first created; and this also was the commencement of the distinction…

Further, it is certain from the context, that the light was so created as to be interchanged with darkness. But it may be asked, whether light and darkness succeeded each other in turn through the whole circuit of the world; or whether the darkness occupied one half of the circle, while light shone in the other. There is, however, no doubt that the order of their succession was alternate, but whether it was everywhere day at the same time, and everywhere night also, I would rather leave undecided; nor is it very necessary to be known. (Calvin 1578, 39-40)

Day and night were both created and defined simultaneously. Day is the not-night, night is the not-day. When there was no day, there was no night either, because there can be no night without a day. Their unity and opposition are simultaneous. It is the same with work and leisure; there cannot be one without the other, because the boundaries of one are defined in opposition to the boundaries of another.

The relation between leisure and the everyday is not a simple one: the two words are at one and the same time united and contradictory (therefore their relation is dialectical). It cannot be reduced to the simple relation in time between ‘Sunday’ and ‘weekdays’, represented as external and merely different. Leisure – to accept the concept uncritically for the moment – cannot be separated from work. After his work is over, when resting or relaxing or occupying himself in his own particular way, a man is still the same man. Every day, at the same time, the worker leaves the factory, the office worker leaves the office. Every week Saturdays and Sundays are given over to leisure as regularly as day-to-day work. We must therefore imagine a ‘work–leisure’ unity, for this unity exists, and everyone tries to programme the amount of time at his disposal according to what his work is – and what it is not. Sociology should therefore study the way the life of workers as such, their place in the division of labour and in the social system, is ‘reflected’ in leisure activities, or at least in what they demand of leisure.

Historically, in real individuality and its development, the ‘work–leisure’ relation has always presented itself in a contradictory way. (Lefebvre 1947.)

We already conceive work only as one half of this division, but it should also be understood as the catalyst of the division too, the light that divided itself from the darkness, so to speak. Taking this into account, it is not to just be understood as one half of the division but the division itself.

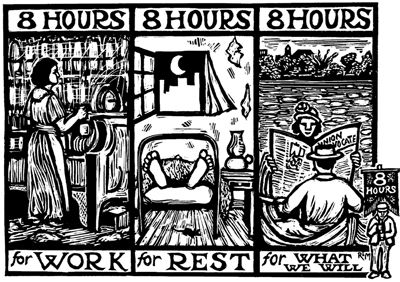

We may take these divisions as something natural and eternal, and point to institutions such as the Sabbath1 as evidence of divine sanction, but we should be careful to precisely consider what we mean by “division”. From a historical perspective, conflicts between labour and capital resulted in the adoption of an eight-hour work schedule:

“The movement to reduce the work-hours is intended by its projectors to give a peaceful solution to the difficulties between the capitalists and laborers. I have always held that there were two ways to settle this trouble, either by peaceable means or violent methods. Reduced hours, or eight-hours, is the peace-offering.” (Parsons 1912)

The unrest that preceded this negotiation should serve as evidence of one thing, and it was that the previous division of time was unsustainable. Work is perpetual by nature, and it was necessary to adjust the division of time to maintain labour’s cooperation.

Why must the spheres of time be exclusive? Because another essential characteristic of work is that it itself is exclusive. Those eight hours spent at work belong wholly to work and none else, the existence of the worker reduced to a machine.

With this division of labour on the one hand and the accumulation of capitals on the other, the worker becomes ever more exclusively dependent on labour, and on a particular, very one-sided, machine-like labour. (Marx 35)

Yet, it is incorrect to conclude that the exclusive nature of work restricts its dominion. Leisure is still defined in relation to work, and is thus governed by it. What the 8-8-8 schedule inadvertently highlights is the exclusivity of each of these spheres of life.

One response to this is an attitude of complete laziness, but what becomes clear is that embracing leisure is no better. Just as night is the not-day, leisure is little more than the not-work.

Due to the success of separate production as production of the separate, the fundamental experience which in primitive societies is attached to a central task is in the process of being displaced, at the crest of the system’s development. by non-work, by inactivity. But this inactivity is in no way liberated from productive activity: it depends on productive activity and is an uneasy and admiring submission to the necessities and results of production; it is itself a product of its rationality. There can be no freedom outside of activity, and in the context of the spectacle all activity is negated. just as real activity has been captured in its entirety for the global construction of this result. Thus the present “liberation from labor,” the increase of leisure, is in no way a liberation within labor, nor a liberation from the world shaped by this labor. None of the activity lost in labor can be regained in the submission to its result. (Society of the Spectacle, Section 27)

Footnotes

- I perform further discussion on the Sabbath and the theology of it within the context of this framework in its own blogpost linked here, with implications that tie into this essay but ultimately aren’t necessary to the main thread of the argument. ↩︎

Blogger and software engineer. I write on tech, politics, and theology.