Note: This essay is scrapped and will likely not be finished. While I think the broad strokes of what I was arguing here was on point, I’m not particularly proud of the essay as I feel as both my style of writing and delivering my points were rather weak here. In addition, I’ve mostly lost interest in continuing it.

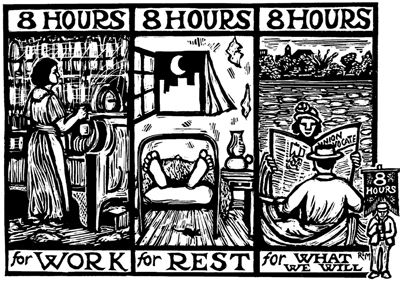

Thesis: Capitalism has horrifically distorted the meaning of work. In light of this, it is absurd to preach “hard work” in a purely individualized sense without first critiquing how work functions in society.

Table of Contents:

Addendum:

Further Reading:

- The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism by Max Weber

- Crisis and Communisation by Giles Dauve

- The Mind of the Maker by Dorothy Sayers

From the very beginning, the question of work versus leisure has generally been considered a stumbling block for Protestant discourse, with preachers often opting to either fall back on old moralisms or ignore the question altogether. Are people getting lazier? Is leisure inherently bad? These are questions Leland Ryken attempts to answer in his book titled “Work and Leisure in Christian Perspective”. Against his contemporaries, he attempts to directly address the question by arguing in favor of a healthy work-life balance.

I doubt that attitudes toward work are very different in our churches than in our culture at large. We find the normal quota of workaholics in the pew on Sunday morning. And what percentage of Christians view their work with the sense of calling that the Reformers proclaimed with such clarity?

The lack of a Christian work ethic is particularly acute among young people. A recent book-length study surveyed attitudes among young people enrolled at Christian colleges and seminaries. One of the conclusions drawn by the researcher who wrote the book was this:

“What has been seen thus far merely confirms what is already well known about the place and value of work for Evangelicalism—that work has lost any spiritual and eternal significance and that it is important only insofar as it fosters certain qualities of the personality.” (Ryken 1987, 13)

Forty years later – well after the generation of the yuppies he derides – Ryken’s position has become the mainstream one. The broader public sees value in the notion of a healthy balance, yet work holds this same drudgery for us. So what gives?

Making sense of this requires us to confront what is quite possibly one of the biggest failures of the modern church: its complete and utter inability to conceive social behaviors outside the context of the individual and some mythical vacuum they’re assumed to exist in. Any time there’s an issue, these preachers always give the same vague responses about “changing one’s attitude, but also not too much, lest you end up going too far in the opposite direction.” Ryken, unfortunately, also falls into the same trap at various points in the book.

The main conclusion this book pushes us toward is a deep appreciation for the provision God has made for human life in the rhythm of work and leisure. That rhythm sounds so simple when we encounter it in the creation account of Genesis and in the fourth commandment that it is easy to miss its significance. Yet all the analysis of the problems of work and leisure in society comes back to the keystone of the goodness of both work and leisure in human life.

Not only are work and leisure goad in themselves, they also balance each other and help to prevent the problems that either one alone tends to produce. If we value work and leisure properly, we will avoid overvaluing or undervaluing either one. (Ryken 1987, 243)

If this is the only thing the church has to contribute regarding the issues that continue to plague people’s everyday lives, no wonder they continue to turn to self-help books and “life coaches” for their problems. After all, they’re offering the same banal and inoffensive advice without needing to confine themselves to any sort of religious affiliation.

This isn’t to say that individual responsibility/agency doesn’t exist, of course it does. To say otherwise would be disingenuous. But at the same time, society is a complex net of relationships between individuals, something which is constantly molding its members yet is capable of developing in a quasi-autonomous fashion. It is based on abstraction upon abstraction, to the point that it can often cause individuals to act against their own nature. This is called “alienation”, and it poses a distinct threat which can’t be explained by simple character traits such as “greed, laziness, selfishness, etc.”

Personal, inner change without a change in circumstances and structures is an idealist illusion, as though man were only a soul and not a body as well. But a change in external circumstances without inner renewal is a materialist illusion, as though man were only a product of his social circumstances and nothing else…

Consequently the ‘coincidence’ of the change in circumstances and of human activity as a change in man himself applies to Christian practice to an eminent degree. The alternative between arousing faith in the heart and the changing of the godless circumstances of dehumanized man is a false one, as is the other alternative, which hinders by paralysing. The true front on which the liberation of Christ takes place does not run between soul and body or between persons and structures, but between the powers of the world as it decays and collapses into ruin, and the powers of the Spirit and of the future. (Moltmann 2015, 34)

The church cannot continue to act as if our religious duty is something that exists on an entirely separate plane from our social environment. To do otherwise is to entirely betray the essential spirit of a missionary religion.

Understanding this requires that we ask ourselves two questions:

- How has church orthodoxy been molded by these external factors, and how can we go about weeding out this revisionism and maintaining the integrity of our doctrine?

- What can the church do towards actively challenging and seeking to alter society? How can we give individuals the necessary autonomy and encouragement to be able to serve God unimpeded?

Returning back to the topic of work, we begin answering that first by question by taking upon a historical-material analysis of work. This may seem irrelevant to a theological argument, but a proper analysis is only possible once we understand its specifically social implications. Failing to do this would only cause us to repeat the mistakes made by countless Christians of the past:

All of this demonstrates that Christians are utterly unable to express revelation in a way that is both specific and adequate for the social reality in which they live. They either repeat timeless formulas (which they take to be eternal), or else they initiate a pseudo-rereading of the Bible: in reality a method of harmonizing biblical content with the dominant ideology. In this way Christians constitute an important contributing socio-political force on the side of the tendency which is about to dominate. As a result, they obtain a small place in the new social order. (Ellul 1988, 14)

Once we have deconstructed and filtered out the secular influences on our interpretation of work, we will be able to turn to the Word to understand what a proper Christian work-ethic should look like.

Blogger and software engineer. I write on tech, politics, and theology.