The following is part of a series of blogposts in which I discuss my design decisions when making the PoliTree: an attempted political-compass killer which has been way too long in the making. To find out more, visit the introduction.

As the test has gone through multiple redesigns over the years, the contents of this post may or may not apply to the test in its modern form.

This is probably going to be the third of a set of pieces I’m doing regarding design choices for the project, not for self-indulgence, but rather instead for the purpose of getting my thoughts back in order following an immense amount of feedback I’ve received.

One of the biggest issues facing the test right now is well… the test itself. While the methodology itself proves effective, it’s an incredibly dense and abstract test, making it difficult for people who aren’t too ideologically conscious to answer the questions; this is an issue because those people are quite literally the target demographic.

So I think it’s for the better I take a step back and think about how to approach this, going over the concepts I’m incorporating and so on.

Why use Marxist concepts?

I stated this in the last piece, but I have no intention to pretend to be neutral here; the decisions I make are ones I feel better reflect the true nature of the topic: there’s no point to trying to do a balancing act for a balancing act’s sake.

However, there is a reason I’m incorporating Marxist concepts apart from solely favoritism. Marxist theory tends to be heavily structuralist and as a result, it’s rather “self-aware” for lack of a better term. There’s a wealth of discussion regarding its priorities, historiography, and contextual placement of the individual, rather than solely discussing proposals and blueprints.

It should be understood that one’s “political position” is not just a suggestion of what should be done but rather instead an understanding of what is going on around you.

So in this sense, so-called scientific socialism is able to act as a template of one specific understanding of society. From there, we can actually extrapolate the model Marxists apply to themselves and see how this can apply to other perspectives and their own understandings of the world.

The Tree Analogy

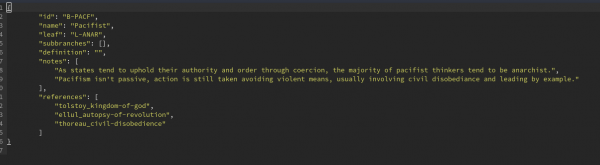

Since the test itself uses a combination of methods, I refer to it and its various components in the context of a “tree”.

The test can be best divided into two halves, the “canopy” and the “branches”.

Like the canopy of a tree, the first part is wide and full of “leaves” that eventually branch down; in other words, the canopy is actually a table, where the answers to two activities form different combinations which we refer to as “leaves”. These leaves, which are on the top of the tree, act as a starting point for the rest of the test.

Once a leaf has been found, a series of conditional yes/no questions are able to give you a much more specific answer. These are called branches because the questions vary based on your answers to previous questions, designed to conditionally “branch out”.

The Canopy: Spheres of Focus

As stated above, the canopy is a table, with the leaves acting as an intersection of two factors: what you believe society is and what you believe needs to be done regarding society.

This section covers the former, namely gauging how the test-taker sees the world around them.

Borrrowing from Althusser’s theories of state apparatuses, we’ll divide societal institutions and relations into one of three categories:

- The Political sphere deals with a society’s ability to maintain its order and stability.

- Words associated with this include: power, influence, coercion, hierarchy, strength, force, conflict, domination, rule, elite, law, justice, violence, peace

- The Ideological sphere deals with a society’s dominant values/narrative.

- Words associated with this include: culture, morals, ethics, values, ideas, discussion, progress, tradition, common sense, opinions, beliefs, art, media

- The Productive sphere deals with how a society handles the creation and allocation of commodities.

- Words associated with this include: economy, currency, production, labor, distribution, resources, trade, exchange, technology

Now that we’ve established the three spheres, the next step is applying them to the test by using them in a question/activity.

The question we will want to answer is: “how do these elements of society interact with each other?”

In order for the test-taker to convey this, I’ve reverse-engineered Marx’s base/superstructure model. For Marx, this model served as a demonstration of his theory that society is fundamentally governed by economic relations.

In abstract terms, the theory goes as such:

- The base is the foundation, the root cause of societal outcomes, serving to shape and guide the direction of the other spheres (the superstructure).

- The superstructure is the reinforcement; it justifies the underlying base that guides it, and ensures that it continues to be maintained.

The neat thing about this model is that it gives a very clear and concise picture of how a communist would understand society. But there’s nothing about the model itself that makes it exclusively communist in nature. By applying the same model elsewhere, we can get a structural model for the worldviews of all sorts of political and ideological currents.

A cleric may see sin as the base of our world, a king may see strength as the base, and so on and so forth. By having the test-taker sort these categories into base and superstructure, we get a better idea of their thought process.

The Canopy: Approach to Society

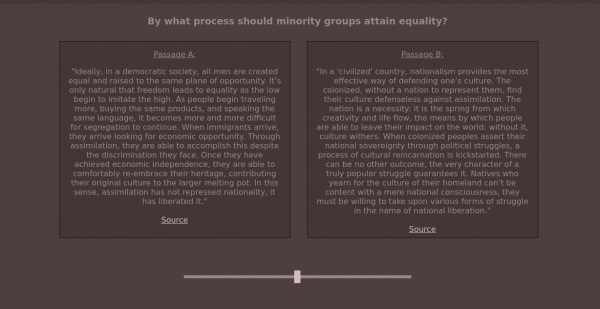

Now that we’ve determined what the test-taker believes society to be, we can begin looking into the other part of the table, what the test-taker wishes to do about it.

This question is two-fold: first the participant has to decide how they see the individual relative to society, more specifically relative to the existing judgement society has made regarding the topic.

The connection between the individual and society manifests itself in the idea of valuation. We refer to valuation in this context as the assigned worth/merit of an individual relative to the greater community.

The valuation of an individual can take one of three forms:

- Innate valuations are judged upon a consistent, inherent, and transcendent standard. This standard is determined by what was selected as the Base.

- Mutable valuations are judged upon a constantly evolving standard; all hold equal potential for value, but that potential may have varying results.

- You can also choose to deny any standard of valuation, seeing the concept as completely Invalid.

The above tells us what the test-taker personally believes about valuation, but we still haven’t connected the test-taker’s conceptions with society’s conceptions.

So the next directive is to understand the test-taker’s position towards society’s conception of valuation:

- Agreement, with the wish to either preserve or slightly reform these conceptions.

- Disagreement, with the wish to control and mold these conceptions to a different standard.

- Rejection, fundamentally criticizing the conceptions with the aim of abolishing the standard itself.

A combination of both of these will give us the next factor of the table. Now by evaluating the answers of both, we can determine a leaf.

The Branches: Narrowing Down

We have the leaf, which gives us a broad idea of a worldview, but we can still get more specific. Luckily since the Canopy narrowed down the field so far, we can complete the rest through a series of specific and conditional questions, utilizing the process of elimination to come to our final answer.

Once we have established a branch, we have finished the test.

Blogger and software engineer. I write on tech, politics, and theology.