Note: Most of the sub-sections under this part are unfinished and likely will not be finished as I have moved on from this essay.

This is part four of a multi-part series analyzing the relationship between Christianity and work. Click here to begin at the introduction and also find the table of contents/bibliography.

Modern Christian attitudes towards work take one of three forms: valorization, pessimism, or moderation. The insight provided by each of these perspectives are incomplete in their own respective ways. What does unite them is the failure to consider the topic not just as a matter of individual choice or some unchanging state of nature, but social organization.

The previous sections functioned as an examination of work through a broader lens, setting context for the matter at hand. Having a historically-grounded basis is what allows us to stress the reality of the matter; it gives the following argument a foundation which goes beyond one of countless purely subjective interpretations of how people should view work.

If the issue was just a matter of culture or attitude, then perhaps we could down some life-coach’s advice like a cheap bottle of wine, but despite how much we wish for that to be the case, widespread alienation remains stronger than ever.

4.1. Work as a Virtue (section incomplete)

And it looks like I’m not the only one who thinks this way either. Christians today can get their advice from the Internet, just a few taps and clicks away from getting a consultation on any moral issue. This is important because it gives us a window into the advice that permeates the mainstream, a look at the thought process of your average person (whether or not this is a good thing is a debate for another day). Within the span of one search, I’ve already come across plenty of articles to work with. Some of these are written by Protestants, some by Catholics, but what ties them together is this understanding that work, not just in the general sense, but in the sense of employment, is a virtue.

We’ll start with the article I picked up from the previous time I drafted this section, giving the topic a broader treatment. This article seems to run through a lot of the points you’d expect, viewing work as challenging but rewarding, condemning sloth, and detailing how it’s part of God’s plan for us.

The author, David Mathis, begins by invoking the cultural mandate as evidence of the inherent goodness of work.

From the very beginning, God created us to labor. “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion . . .” ([Genesis 1:28](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/Gen 1.28)). Work is not the product of sin, but a major facet of God’s original plan for human life in his world.

Right off the bat, this raises some questions. Were Adam and Eve really called to work in the same way that we understand now? Is this understanding of work consistent with the way in which work is presented through the rest of Scripture?

I scarcely know a biblical text which presents work as valuable, good, or virtuous. It is necessary to be clear on this. In the Bible work is a necessity, a constraint, a punishment. except in a few, unusual texts. Of course, everyone knows the story of Genesis 2, in which humanity, before the break with God, was called cultivate and to guard the Garden of Eden. Hence, the whole battery of theologians who find in this text the origins of work and who thus claim to have proof that work is part of human “nature”. What I would like to point out, however, is the paradox that this original notion includes none of the characteristics of work! True, cultivation is required, but it has little utility, because the Garden already flourishes on its own without any particular human help. Also, it is necessary “to guard” the Garden, but from whom? We will not enter into a debate on the preexistence of evil in creation; of this evil I find no trace in the Bible. There is no enemy there, no “principle of evil”, no Satan. There is only the serpent, not a mythical or metaphysical serpent, just a simple animal. Nevertheless, Adam is told to cultivate and to guard, to concern himself with functions perfectly useless and unnecessary. This is neither law, constraint, nor necessity. At the same time the distinction between these activities and play does not yet exist. One is not able to speak of work in the ordinary sense.

When we go to the next verse (Genesis 2:16), the garden is clearly one of abundance, where Adam is capable of feeding himself with fruit from any number of trees. There’s no mention of the sweat of his brow or thorns and thistles. Maybe one could argue that the difference between Genesis 2 and 3 is that in 3, the land is more hostile. But the sort of agricultural labor Mathis imagines Adam performing exists precisely because the land is hostile. The Garden is self-flourishing, and as Ellul states, it’s difficult to distinguish between work and play in this context.

The rest of the article is dedicated to the example of the Apostle Paul, and the steadfastness he showed in his mission.

There is a word of hope here for those who battle laziness. Paul professed again and again that the key to his seemingly tireless labors was God at work in him ([Philippians 2:12–13](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/Phil 2.12–13); [Colossians 1:29](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/Col 1.29)). It was not in his own strength to do what he did. Christ was strengthening him ([1 Timothy 1:12](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/1 Tim 1.12); [Philippians 4:13](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/Phil 4.13)). In the same breath, he says he “worked harder than” the other apostles, and he says, “though it was not I, but the grace of God that is with me” ([1 Corinthians 15:10](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/1 Cor 15.10)). And still today, Christ strengthens his church by grace ([Romans 16:25](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/Rom 16.25); [2 Timothy 2:1](https://biblia.com/bible/esv/2 Tim 2.1)).

And, this is where I think the semantics of the issue really begin to have an effect, which is why I gave so much time to articulating and defending an alternative definition of work. If we define work as a generic catch-all term for any sort of task conducted with effort, we run the risk of neglecting the various nuances associated with it on both historical and political planes.

The same can be extended to the label which the author bestows upon Paul: hard-working. What does it mean to be hard-working? Is a man who spends half his day in the factory and half his day drowning himself in alcohol not hard-working? Could not the same be said about the slaves who spent their lives working in the Roman salt mines? The answer is, yes they are hard-working; but their situation isn’t inspiring, its pitiful.

So, what separates Paul from them, if effort and time aren’t the central characteristics? Let us take a minute to think what kind of words can describe the example he set forth for Christians: persistence, courage, discipline, patience, humility (Romans 12:3-8): the list goes on. These characteristics remain so striking to us thousands of years later because this was not some task he took up reluctantly. What sets apart Paul’s mission is not the way in which he approached it but the nature of said mission. When Paul sets sail for Rome, his resolve testifies not to any personal greatness he has but rather instead the power of he who sent him and what he has been sent out to do.

4.2. Work as a Curse (unfinished)

4.3. Work as a Balance (unfinished)

With the 20th century, we began to see a lot of these debates between capitalism and socialism, individualism and collectivism take place.

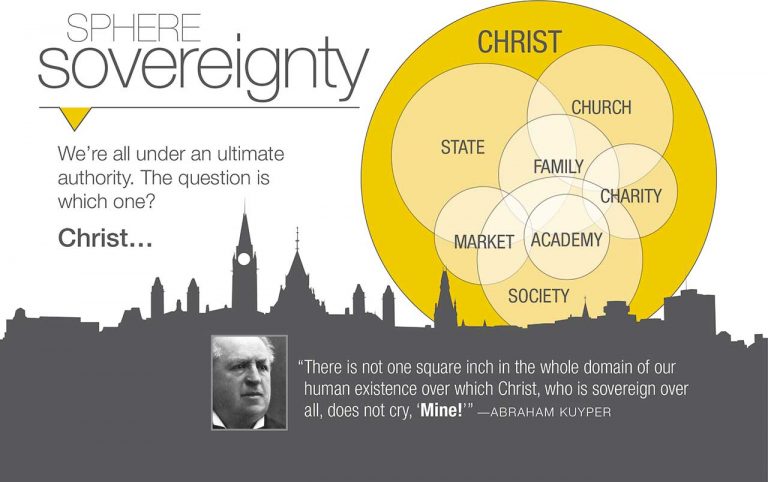

Leaders of the Dutch Reformed movement (most notably Abraham Kuyper) attempted to meet these problems with a new theory of social relations. Looking to strike a middle ground between a full church-state (as was the case with various medieval Catholic societies) and the complete secularization of liberal societies, Kuyper developed the concept of “sphere sovereignty”.

Kuyper’s Third Way between the evils of popular-sovereignty, on the one hand, and State-sovereignty, on the other, was sphere-sovereignty—or, as he called it himself, “sovereignty in the individual social spheres.” For Kuyper, society was made up of a variety of spheres, such as the family, business, science, and art. They derived their authority not from the State, which occupied a sphere of its own, but from God, to whom they were directly accountable. Each of the spheres developed spontaneously and organically, according to the powers God had given them in the first moments of creation. (Heslam 2002, 17)

The idea behind sphere sovereignty is that society can be broken down into relations, each of which fall into various categories, known as spheres. The workplace may be one sphere whereas the household may be another. These spheres have their own norms, hierarchies, and purpose in both social and individual life. In order to best carry out the Christian duty, no one of these spheres should intrude on the other. Through this balancing act, Kuyper hopes that the ideal of doing all to the glory of God (1 Corinthians 10:31) could be realized.

But there was a dual meaning to this concept of sphere sovereignty, not just in the conduct of the life of the individual, but also society as a whole. Kuyper, being the Dutch Prime Minister and the founding father of a major political party (the ARP), was able to see his theory implemented into practice. Building off of his ideas, the Dutch developed a system of “pillarization” in which their nation was divided up into multiple sub-societies. Within pillarization, society would be divided up into various political/religious groups (Protestant, Catholic, socialist, etc.) each with their own set of institutions. Each group was given space to cultivate their own schools, media outlets, hospitals, unions, and so on.

Kuyper attached, however, a secondary meaning to his idea of sphere sovereignty. This was the notion that confessional or ideological groups in society were free to organize their own autonomous institutions. As rector of the Free University he called for orthodox Protestants to separate themselves from the rest of society to develop an independent sphere of life (levenskring). “We wish to retreat behind our own lines,” he declared, “in order to prepare ourselves for the struggle ahead.” The argument found backing, Kuyper claimed, in those ideas of his intellectual mentor Groen van Prinsterer, that were encapsulated in the motto: “In isolation lies our strength” (“In het isolement ligt onze kracht”). (Heslam 2002, 19)

It stood not just as a way to mediate competing interests and give every religious group space to properly thrive, but also as a bulwark against the secularizing forces that were beginning to dictate every aspect of life and social organization since the Enlightenment. It affirmed the religious character of society in a time when people increasingly began to understand it as something purely mechanical or abstract.

Clearly Kuyper’s theory was based on an organic understanding of the nature of society. As such, it was a response not only to individualism but to the mechanism and scientism prevalent in the intellectual world at the end of the nineteenth century. In opposition to these latter two theories, which taught that society is governed by neutral forces that operate in terms of cause and effect, Kuyper argued that society should be understood as a moral organism. (Heslam 2002, 17)

However, also in this plan, we can see the connection between his vision for both individual life and social life. He correctly understood how the two were connected, that how one approaches the day-to-day and how one interacts with their neighbors feed into each other. Society is not merely the sum of its individuals, but it is also not entirely detached from the individual experience.

At the heart of his thought lies not the human individual but the human person with the complex matrix of relationships that belong to true personhood. Hence, his stress on the group and on the organic way in which groups, or “communities,” operate and develop. He understood society as a relational entity, and his model of society is a persons-in-relation model. It is this balance of the person and the community that underlies the respect that the German theologian Ernst Troeltsch displayed toward Calvinist social theory. (Heslam 2002, 25)

And at a glance, it really does seem as if departs from the principle laid out in his famous quote. (“There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”) That principle is wholly admirable, and something I agree with, but I

4.4. Towards a New Work-Ethic

In the end, we still have to speak of a work-ethic in some positive sense: not so we can somehow learn to love our 9-5 schedule, but so there can be an actually existing movement to speak of. If we are to assign activity an existential importance, then it makes itself manifest in all aspects of life and society.

This also goes for revolutions. For far too long have socialists been content to concern themselves with questions of distribution: how are we going to deal with inequalities in wealth, who is going to own what, who is stealing from who.

Production, and by extent work, is treated as a simple means to an end: the structure of our day-to-day lives isn’t altered, society is expected to continue on as it did before minus some reshuffling of cards. In this sense, their mentality is no different from that of the capitalists. This mentality has been entirely outmoded by the welfare state, which provides the aforementioned reshuffling but in a more orderly fashion.

But as we’ve seen in the above sections, work is so much more than that. It’s dynamic, its the link between potential and actuality, the purest expression of will. Work is creation.

Work in the Bible begins with God’s work of creation. God’s work of creation is obviously not toil. It is mote like play or the exuberance of the creative artist. It is joyous and energetic, unencumbered by the need to overcome obstacles or wrestle the physical elements into a finished product. Yet the activity of God in creating the world must be considered work. We know, for example, that after six days of creation “God finished his work which he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had done” (Genesis 2:2). In the actual account of creation, moreover, God rests from his creative work after each day, setting up a rhythm of work and rest. (Ryken 1987, 120)

We have spent the last three-hundred years erasing this fact, suppressing the most vital of aspects to our existence. Instead we have created a culture in which we live vicariously through our consumer goods, one where one can only live as a spectator. Is it any surprise that when we treat work as an obstacle, that people will seek to avoid it? What does it tell us that our rejection of what is most essential to us is rooted in fear and complacency?

In our society, man is being pushed more and more into passivity. He is thrust into vast organizations which function collectively and in which each man has his own small part to play. But he cannot act on his own; he can act only as the result of somebody else’s decision. Man is more and more trained to participate in group movements and to act only on signal and in the way he has been taught. There is training for big and small matters—training for his job, for the driver and the pedestrian, for the consumer, for the movie-goer, for the apartment house dweller, and so on. The consumer gets his signal from the advertiser that the purchase of some product is desirable; the driver learns from the green light that he may proceed. The individual becomes less and less capable of acting by himself; he needs the collective signals which integrate his actions into the complete mechanism. Modern life induces us to wait until we are told to act.

Man is a product of his environment, and modern man is characteristically modern. His cowardice, indecision, complacency, passivity, and entitlement all allow him to thrive in this environment. Of course, these have all been inherent to humanity since the beginning of time, but there remains another fact about man which is just as timeless: in social life he finds his justification. His moral compass is trained on what he sees in his peers, his eyes are trained on the path of least resistance. This attribute allows us to stably co-exist in societies but it also means that individuals embody the attributes of the societies they live in.

And it just so happens that industrial and capitalist societies happen to be defined by commodities. To us, the product rather than the process is what matters. We spend our time looking for ways to save time, we enter the office fixated on the clock. When the time comes to rest, the clock still looms, only counting down the hours with dread rather than anticipation. The only way we can afford this is by giving every aspect of life its own private sphere which it cannot overstep: the family gets night-time, God gets Sunday, the job gets the day.

And if that’s what’s dominant, if that’s what occupies our thoughts, then that must be what we fight against as Christians. We stand against the world, and while that relationship remains unchanging, whichever idol currently demands our attention has always been subject to flux. They come and pass, never able to measure up to the Eternity they claim. The task remains the same as it always has: to unmask all that presents itself as inevitable, all that demands our undivided attention. The world is willing to grant religion its bubble, a place to be slotted in only after all other considerations of time, politics, logistics, and economy have been hashed out. All this and not an inch more. But it is up to us to resist the temptation of integration.

Only through the ruthless criticism of all that exists — a truly radical negation — can the light of the Gospel come to penetrate every aspect of life. Before God, the duplicity of time fades away, life reveals itself as a unified, undivided stream of pure existence. Man, looking past all earthly abstractions and loyalties, stands in a direct, intermediated relationship with God.

Our minds are not infinite; and as the volume of the world’s knowledge increases, we tend more and more to confine ourselves, each to his special sphere of interest and to the specialised metaphor belonging to it. The analytic bias of the last three centuries has immensely encouraged this tendency, and it is now very difficult for the artist to speak the language of the theologian, or the scientist the language of either. But the attempt must be made; and there are signs everywhere that the human mind is once more beginning to move towards a synthesis of experience. (Sayers 1941)

This is not something which can be accomplished with a mere shift in cultural or individual attitudes. No amount of reflection will change the fact that without the wage there is no survival, that the reproduction of this society is something that’s expected out of all of its members. Refusal is not merely punished, but rather instead granted as impossible. Our perspective can only spur us to action, the renewal of the self under salvation creates a will to see the renewal of the world.

Just as social critique absent of individual critique can often shield men from acknowledging the weight of their own sins, the reverse also holds true. The Tower of Babel reflects the character of its builders; institutions of man are no less fallible than men themselves. If we erect a barrier beyond which our critique cannot be extended, can we truly say that it holds a radical presence?

We struggle for this not because we expect sin to be eradicated by socio-economic change, not because we believe the Lord has predestined us political victory in some millenarian fashion. We struggle because the means and the end are simultaneous, each and every moment contains historical potential. Christ has overcome the world, that much was accomplished on the cross. To many, this fact seems to lend itself to complacency, but the example of the apostles shows us the opposite.

Christ is victorious, this means we have nothing to fear. Christ is victorious, that means that no matter what happens, we have no reason to resign. Christ is victorious, that means that even in the face of momentary defeat, the Gospel will be preserved, others ready to carry the torch. It fills us with a restlessness, an eagerness to participate in the saga of mankind’s redemption.

Liberation theologies throughout history have chosen to focus on some arbitrary future hope, some point at which everything falls into place. Because of that, it has found itself generally in concord with programmatic variants of socialism, which promise just that in exchange for present party adherence. Deferred enough, this hope becomes an un-reality, a future so distant that it may as well constitute an alternate universe. The mistake is failing to recognize that the hope is in front of us.

We might be tempted to approach the problem from the other side and list all the reasons not to revolt, chief among them the enormous repressive power of the state. Most revolts end in failure, even if we define success in the most modest terms, and failure means, let’s be clear, not only wasted effort but injury, death, imprisonment. Except in situations where survival is truly at stake, there is always good reason to keep one’s head down, to stagger on under the nightmare weight of history. But fear explains both too much and too little, since many do revolt in situations when the odds are not particularly good and the risks great. At a first pass, we are confronted by an insufficient positive explanation (reasons for) and an insufficient negative one (reasons against). Moreover, as nearly all commentators have noticed, since the odds of success for a revolt are not determined by the force of the enemy alone but by the number of those who participate, there is something circular and self-fulfilling about whatever judgments participants make about the risks. Bad odds can be transformed into good ones if, by misapprehending the situation or ignoring the risks, some small group decides to go ahead anyway, creating felicitous conditions for everyone else. A leap into the void can make the ground appear, just as a refusal to leap can turn solid ground to thinnest air. (Bernes 2020, 193)

It is here the essentially spontaneous character makes itself known. As said before institutions reflect the character of their architects, this is the same for revolutions. If revolution is defined as means to the end, a provisional situation which is to be tolerated until the bureaucrats bring about utopia, then it will indefinitely wallow in whatever it has actually achieved. The product once again takes precedence over the process. This was the case for the Soviet Union, which during the post-Stalin era, languished in corruption, un-ambition, and drab mediocrity.

There has never been a golden age, there never will be a golden age. We cannot expect socialism to solve every problem of human nature, logistics, or philosophy, but we don’t need to. Our world has always been a hellhole and will always be, just in respectively different ways. It’s still our hellhole, and we will still continue to persist, no matter the conditions. We exist in this reality no matter how absurd it is, same as our forefathers.

Does this mean we should give up the task of radical social transformation? No, quite the opposite. There is nothing for us to wait on, nothing for us to fear, nothing for us to settle for, nothing for us to resign to. This world has been wholly corrupted by sin, but Christ has overcome the world. (John 16:33) If anything the good news is vibrant, it’s energizing. It calls a person to carry out their duty to the Lord without hesitation, unwavering in commitment and drive.

This leaves us not with contentment but complete confidence. Modern radical movements have been entirely rattled by the end of history. Terrorists, in a mix of cynicism and panic, blindly kill in the hopes of history remembering them as a tragic hero. Electoralists settle for “harm reduction”, having subconsciously given up on anything more ambitious than damage control. The parties and organizations of old continue to panhandle for power, idly fantasizing about all the things they can do with sufficient political leverage.

Revolution is the ends making themselves known through the means, a simultaneous process of destroying and prefiguring, a movement which incubates its own conditions. The re-kindling of social bonds in a currently atomized world, the creativity in insurrection which paves the way for actual social organization, the unapologetic self-indulgence which forms a basis for an authentic collectivity. It is inherently social, there is no deferring this. If there are no feelings of sociality, nothing in the movement itself apart from its results, it will inevitably be consigned to the dustbin of history. Certain conditions and crises can set the stage for it, but the spark is still ultimately pure collective will.

4.4a. Why Christianity? (unfinished)

This section is optional (as signified by the “a” in the section title), you can skip to the Bibliography if you want to continue the main thread of the argument.

Through this essay, I’ve given a lot of focus to defending Marxism from a Christian angle, but the reverse is often just as contentious a topic.

I want to make it clear that first and foremost I am a Christian. The paradox of the cross is the a priori axiom through which I understand everything else. I am concerned first and foremost with the salvation from mankind from itself,

Often in these sorts of arguments, you’ll see Christian Marxists go on about the ways in which Christianity benefits Marxist ends, their shared principles, or how what a person believes doesn’t matter. This is incredibly shortsighted, and only exacerbates the dissonance, even if it gets other Marxists off their back about their faith. After you’ve sufficiently performed apologetics for the faith, what actual substance is left of the faith?

How much simpler it would be not to deal with all this! But our Marxist Christians would not dream of abandoning their faith; they feel a sentimental attachment to God’s revelation, and would suffer traumatically if they eliminated the label from their lives. They prefer to reconcile and rationalize. Falling prey it) a process repeated throughout history, they claim to safeguard Christianity’s authenticity by selecting from it those elements that can be made to coincide with the prevailing ideological movement of the day: in this case, Marxism.

Ignorant of history, they fail to realize that this process has been tried a thousand times, for the purpose of restoring Christianity’s authenticity. Always it has appeared extremely helpful, but without fail it has produced catastrophe for faith and the revelation. How much better it would be to blot out the Bible and Christ, abandon them once and for all, and thus be able to limit one’s efforts to “serious matters”: politics, the economy, revolution, the Third World, and the oppressed classes. (Ellul)

If Christianity is supposed to be merely some liberatory myth, some tool to advance a political cause, then the next question is what do we even mean by Marxism? Do we mean the ideological tradition of proletarian revolution as espoused by the likes of Marx, Engels, and Lenin?

If so, then how do we grapple with the fact that this tradition has long been, in Lenin’s words, “atheistic and positively hostile to all religion”. And for those who reject Lenin, we can even point straight back to Marx in his famous quote:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

Even when we look at the broader context of this passage there is no getting around the fact that religion cannot be merely used as a tool for liberation.

When Marx states that “the struggle against religion is a struggle against the world”, he does so with an understanding of Religion as the consecration of all things worldly. This is not a metaphysical but an anthropological statement: the point of interest is how religious institutions and ideas integrate into mainstream society. Whether or not a God exists or what form that God takes is besides the point for Marx, because irrespective of that answer, the world is the world. We can see how the world functions for ourselves, the church doesn’t need to tell us how our eyes work. Marx’s aim is not to disprove the existence of higher truths, but to show how refusing a material analysis to material reality only amounts to obfuscation regarding said reality.

But man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man – state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopaedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d’honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal basis of consolation and justification. It is the fantastic realization of the human essence since the human essence has not acquired any true reality. The struggle against religion is, therefore, indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.

It is, therefore, the task of history, once the other-world of truth has vanished, to establish the truth of this world. It is the immediate task of philosophy, which is in the service of history, to unmask self-estrangement in its unholy forms once the holy form of human self-estrangement has been unmasked. Thus, the criticism of Heaven turns into the criticism of Earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.

All of this so far only testifies to the negative essence of Marxism. We can see what Marx recognizes as existing and how he criticizes that which exists. But what fills that void? Is it some belief that the material is somehow superior or “more real” than the spiritual? Is it that the political programme of the proletariat is some supreme good to which individuals are morally obligated to subject themselves? No, because if we were to distill some sort of “pure Marxism”, it would be fundamentally negative in nature. It can explain tensions, it can show contradictions, it can provide tools for analysis but Marxism alone is not a metaphysical or existential prescription.

That’s not to say Marx didn’t have a philosophic foundation. His arguments against capitalist society were downstream from a secular humanist tradition which stretched from the beginnings of the Enlightenment to the Hegelians of his time. This philosophy was implicit through his writings, as the values espoused by them were taken for granted by both the people he was interested in engaging with and the larger cultural environment in which he existed. He did not need to re-litigate the inherent goodness of humanism, that would only be redundant. Instead, his concern in this respect was showing how the mechanisms of capitalist society are an obstacle to the humanist ideal.

Socialism is a means to an end, rather than the end in and of itself. The mistake in these discussions is that the framing essentially puts the cart before the horse. Christianity when treated as something ancillary becomes little more than a cultural or political mantle-piece, its entirely gutted of any sort of subversive content. Marx witnessed this in his time, and we see it in our time with the countless “conservative” and “progressive” Christianities which are near indistinguishable from their secular counterparts.

Socialism when treated as an end unto itself denies agency to the individual; it defers any hopes of meaning or fulfillment until their external environment has changed. It demands the individual view himself as a historical subject as opposed to a historical agent, waiting upon history to happen to him rather than making his mark upon history. It justifies atrocities and compromises by deferring the question of fulfillment or meaning to an arbitrary future state. It produces martyrs, not human beings. Ironically, this approach to socialism is the epitome of what Marx characterizes as religion; a social opiate which renders men passive by detaching themselves from their present situation and self.

Blogger and software engineer. I write on tech, politics, and theology.